Taxonomy

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Mammalia

Order: Carnivora

Family: Ursidae

Genus: Ursus

Species: arctos

Scientific Name: Ursus arctos

IUCN Red List Status: Least Concern

About

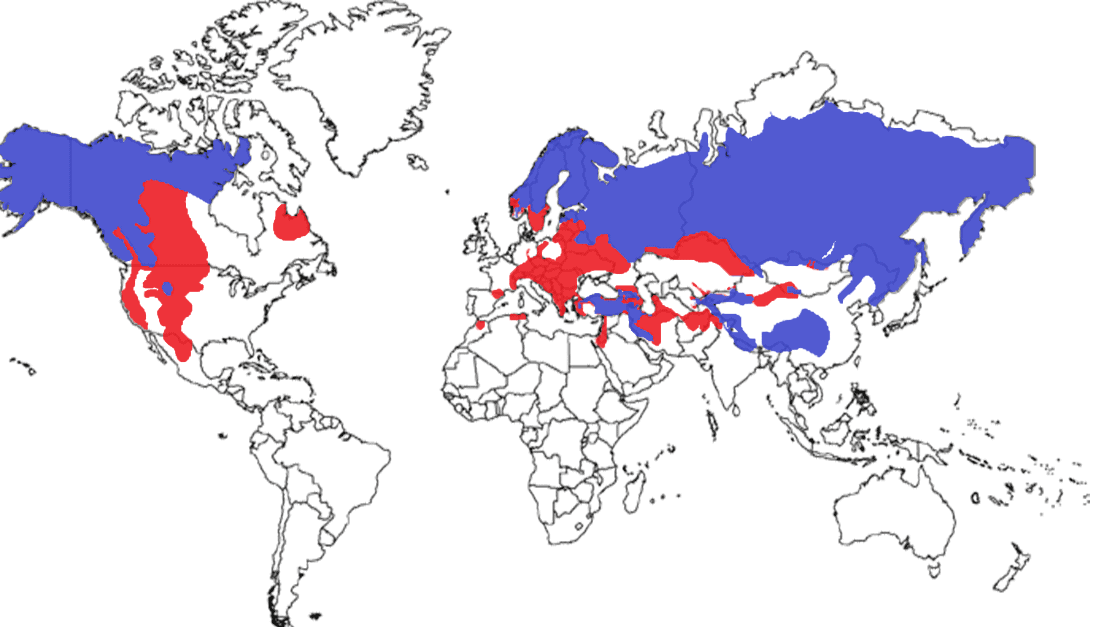

Habitat: Brown bears are one of the most widely distributed bear species in the world. They can be found in multiple regions and, therefore, many different biomes. Ranging from Arctic tundra, boreal forests, coastlines, alpine meadows, and mountain woodlands, a brown bear’s necessities include access to plentiful food sources and areas of dense cover to shelter them during the day.

Recognized Subspecies

Caucasian brown bear – U. a. meridionalis

East Siberian brown bear – U. a. yenisensis

Eurasian Brown Bear – U. a. arctos

Grizzly bear – U. a. horribilis

Kashmir (Himalayan) brown bear – U. a. isabellinus

Kamchatka brown bear – U. a. piscator

Kodiak brown bear – U. a. middendorffi

Syrian brown bear – U. a. syriacus

Tibetan brown bear – U. a. pruinosus

Ussuri brown bear – U. a. Lasiotus

Territoriality: Brown bears are typically solitary animals, but they will congregate in larger groups around plentiful food sources, like annual salmon spawning. During these group feeding frenzies, a social hierarchy is established between the bears. The largest adult males being the most dominant, but the females with cubs are the most defensive and dangerous. Outside of these gatherings, the only social interactions will be between mothers and cubs. Although territorial, their home ranges can overlap, and boundaries aren’t always enforced. A male brown bear can cover a territory of up to 500 square miles, but females will usually only occupy about 50 to 300 square miles. To maintain these territories, bears communicate with sounds, smell, and movement. They mark their territory by rubbing their bodies against trees, stomping urine into the ground, as well as scraping trees and defecating.

Lifespan

In the Wild: Up to 25 years

In Captivity: Up to 40 years

Population

Less than 200,000 individuals

Physical Description

Weight: 400 – 1200 pounds (depends on sex, age, season, and region)

Length: 5 to 8 feet

The coat coloring of brown bears relies heavily on environmental conditions, such as climate and diet. These conditions are dependent on the geographical areas in which the bears are found. Although their fur is typically dark brown, it can also be a variation of white, blonde, red, or black. Brown bears are also easily discernible from their American black bear cousins because of their large shoulder hump. This hump is a large muscle that helps the bears be powerful diggers. Brown bears are also equipped with extremely long claws. These claws are an average of three to five inches long and are shaped like shovels. Brown bears are sexually dimorphic, meaning that males and females differ significantly with their sizes. Males are much larger than females, but size also depends on the subspecies of brown bear. The largest brown bears, Kodiak bears, exist in the Alaskan Peninsula and can weigh over 1,000 pounds.

History

Prolonged overexploitation in Europe resulted in the eradication of brown bears from many countries. Brown bears located in North Africa were extirpated during the 1500s from Egypt, as well as Algeria and Morocco in the 1800s. They had thought to not exist within the Middle East, although recent sightings have found bears in western Syria.

In North America, brown bear populations used to be at a higher volume with a broader distribution across the continent. It is estimated that in the early 1900s, there were 100,000 grizzly bears across the United States. These bears were nearly driven to extinction after gold was discovered in the mid-1800s, and humans began populating and developing the western United States. In the 75 years that followed the California gold-rush, the nearly 10,000 bears that lived in the state previously had been reduced to none. The last California grizzly bear was shot in 1922, 30 years before the brown bear was named the official state land mammal of California.

Currently, brown bear populations are stable, due to the increased number of conservation and education tactics of both nationally and internationally governing bodies.

Reproduction

Gestation: 180 – 270 days

Litter Size: 1 to 4 cubs (2 average)

A brown bear will typically reach sexual maturity between the ages of four and six. But, females have occasionally been known to give birth as early as three years old and as late as ten years old. Breeding season is very competitive, with males fighting for breeding rights of a single female. A female can potentially breed with many males in a single season; one particular male might guard a single female for a period of up to 3 weeks after mating. Brown bears typically breed from mid-May to mid-July, but the female will delay the embryo being implanted until late fall when they begin entering their dens. This delayed implantation will depend on the amount of fat the female was able to store before winter. If it is not a sufficient amount to ensure the survival of both herself and her potential cub(s), the embryo will not be implanted, and the female will not become pregnant that season.

Mother brown bears are very protective of their cubs and are considered extremely dangerous to both people and other bears. After birth, the cubs will be nursed until spring, when they emerge from their winter denning. A mother will raise her cubs for two to four years, during which the mother usually does not mate.

Diet and Hunting Behaviors

Brown bears are apex predators, meaning they sit at the top of the food chain. But, they are also omnivorous, eating both plant materials and protein. Their diets depend significantly on season, region, and habitat. But consist of grasses, berries, fungi, roots, nuts, fruits, honey, and fish. Brown bears will also hunt mammals like rodents, mountain goats, cervids, or deer species, and sometimes carrion. Most brown bear species’ diets consist of 80 to 90 percent vegetation.

In the late fall, a brown bear can eat 90 pounds of food per day. This increased feeding is to pack on as much weight and fat stores as possible for the coming winter denning. They will typically go into their dens weighing twice as much as when they emerge in the spring, as they can lose 150 pounds over the winter.

Bears Are Not True Hibernators

A bear’s winter sleeping can be called a variety of things, depending on where the information is found. These names can include shallow torpor, dormancy, hibernation, or winter lethargy. During this time of inactivity, the bear’s heart rate decreases, its metabolic and breathing rates will slow down, and its body temperature will drop. But when it comes to bears, they are too large to go into a state of true hibernation. Their body temperature will only lower by about 10°F; smaller mammals who will exhibit true hibernation will drop their body temperatures by about 60°F.

Bears are adapted to survive inactivity for up to five months in the winter. While inside their winter dens, they do not consume food or emit waste. A bear’s body will change, to prevent their bodies from poisoning themselves with all of their waste, so that their kidneys can process this waste. Because they do not eat after entering their den, they lose about 10 to 15 percent of their body weight. If a human were to stay in bed for five months, they would lose lots of muscle mass; a bear’s body is hardwired to prevent this from happening. They will experience micromovements throughout their winter denning to prevent atrophy, or muscles wasting away. They are also able to process urea, a component of urine, to build new proteins and help to maintain their muscle and organ tissue.

Fun Facts

- Alaskan brown bears have been known to dig “belly holes” so that they can lay down comfortably without squishing their large bellies after eating lots of food!

- A group of bears is called a sloth or a sleuth!

- Brown bears can run up to 30 miles per hour!

- The name “grizzly” comes from the white/gray tips on their coat.

- The taxonomic subspecies name, horribilis, was influenced by an interaction that Lewis and Clark had with a grizzly bear.

Threats and Conservation

As a whole, brown bear populations are stable. But, several threats still affect their populations across the world. Small isolated populations, like those in the lower 48 states, are low in numbers due to frequent contact with humans. Increased human population can lead to many threats for brown bears living in those areas. These threats can include habitat loss and fragmentation, the higher likelihood of human-wildlife conflict, a decrease in food sources, and illegal hunting. As the human population increases in an area, urbanization and development encroach more on natural habitats. Brown bears are wide-ranging omnivores that are easily attracted to human food sources that are frequently found in these well-populated locations. Bears that become reliant on human food sources such as garbage, livestock, and wildlife feeders for birds and deer, can potentially be categorized as nuisance bears and euthanized as a preventative measure. Finally, in smaller, isolated populations, illegal hunting can be detrimental because brown bears have an incredible slow reproductive rate. They are not able to successfully “bounce back” once they have been reduced.

In countries where brown bear populations are large and contiguous, the bears are hunted for sport or population control purposes. While this mandated hunting can be an effective way to maintain high prey populations (i.e., moose, elk, and caribou), it can also become a problem when hunting limits and regulations are not followed. Over-hunting and illegal hunting can limit genetic diversity and hinder population growth.

The conservation concerning brown bears is dependent on the region or nation in which the brown bears reside. Because brown bears are the most wide-ranging bear species in the world, they have a wide range of conservation efforts and laws that pertain to them. These efforts include complete international species protection, habitat protection, and management tactics.

In certain regions, like China, Mongolia, and Pakistan, brown bears are listed under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). CITES was created as an international agreement between countries to ensure the international trade of plants and animals does not threaten their survival.

Habitat management is another critical action that is being taken by some of the areas in which brown bears live. Specifically, in the United States, Southern Canada, and Western Europe, strict reintroduction and habitat connectivity management have benefited populations.

Many areas with large populations manage the species as a legally hunted game animal, including Russia, Japan, Canada, Eastern and Northern Europe, and Alaska. These areas have strict regulations pertaining to the animals being hunted. Bag limits, hunting seasons, and animal parameters are in place to ensure a sustainable management plan. The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) in the United States and Canada works to conserve bear populations and natural habitat by forging partnerships with businesses to ensure adequate management is in place.